By "W"

thursday, november 21, 2024 at 12:14:17 a.m. est

"seven days of hell in new orleans"

Pedro Gonzalez from Contra<contra@substack.com>

wed, nov 20, 2024 at 9:07 p.m.

"seven days of hell in new orleans"

"a black nationalist hunting for whites struck fear into the heart of Louisiana. it took a rogue Marine who commandeered a helicopter to stop him.

Pedro L. Gonzalez

nov 21

preview

Note: I poured my heart and soul into this one, so I hope you enjoy it. If you're a new reader, welcome to Contra. If you've been here for a minute, please consider upgrading your subscription to paid. It helps me do more long-form writing like this.

New Orleans, 1972.

Drunken cheer resounds through the French Quarter on New Year's Eve. As revelers dance through the streets and prepare to turn the page, a blue 1963 Chevrolet pulls up a block from the headquarters of the New Orleans Police Department.

The engine rumbles off. Mark Essex alights in the night with a green duffel bag along Perdido Street. He is packing a Ruger .44 Magnum carbine, a .38-caliber revolver with the serial number filed off, a gas mask, wire cutters, lighter fluid, matches, and firecrackers. Essex is a young black man with murder on his mind, and tonight, he will fire the first shots in a weeklong spree targeting white people with the aim of starting a revolution.

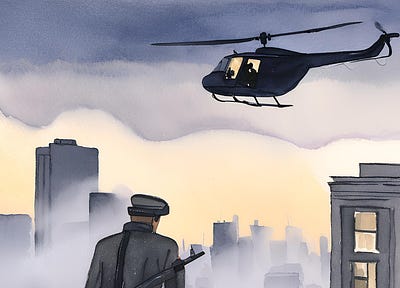

When the killing stopped, eight would lie dead by Essex's hand, including three police officers. His rampage only ended with the intervention of a rogue United States Marine Corps pilot named Charles Pitman, who commandeered a helicopter without military authorization to help hunt Essex.

This is the story of the New Orleans Sniper, the seven days of hell he visited upon that city, and the uncommon valor of the man who risked his life and career to save others.

I've long wanted to write about this episode of American history in no small part because I was raised on Die Hard, and Pitman struck me as a "Yippee-ki-yay, motherfucker" kind of guy. When "Chuck" died of cancer in 2020, he was a retired lieutenant general who had flown 1,200 missions in Vietnam, survived being shot down seven times, took an anti-materiel rifle round to the leg, and played a part in Operation Eagle Claw. But he said the thing he was proudest of in life was having helped take down Essex.

New Orleans showed its enduring gratitude to Pitman by making him an honorary police captain in 1991. The Marines rewarded him with a threatened court-trial for "borrowing" a helicopter. The issue was thankfully resolved when U.S. Rep F. Edward Hébert, a New Orleans-based Democrat and then chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, lobbied on Pitman's behalf.

Harvey Mansfield once defined manliness as "confidence in a situation of risk," a quality he argued has been in short supply in the West of late. Pitman had that and then some. A harder American you would be hard-pressed to find. Pitman deserves to be honored, and I want to do that here.

Another reason I find this story fascinating is that it seems to have been virtually memory-holed, despite the fact that it captured national headlines and influenced the way police would handle these scenarios in the future. This was a deeply traumatic event for Americans at the time.

It briefly jumped back into the public consciousness in 2016 when a black military veteran targeted white police officers in Dallas, Texas.

Tom Casey, a retired member of the New Orleans Police Department, watched the carnage unfold in the news and was returned to that awful day. "I never met any Dallas cops, but I felt like they were my brothers," he told The Advocate. "And I felt the same watching that on TV as I did in that helicopter." Casey was among the officers who joined Pitman on the chopper that fateful day.

I should note that Peter Hernon's A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper is an incredible book. It was one of many resources I used for this story, but easily the most indispensable one. It's a sterling example of real, old-fashioned journalism.

You'd have never guessed Mark James Robert Essex would someday be a crazed Pan-African nationalist shown the door by prominent Black Panthers who dismissed him as "beyond crazy." There had been little in his upbringing to presage a cold-blooded killer. He was, as Cormac McCarthy described the murderous Lester Ballard, a "child of God much like yourself perhaps." So then again, maybe there had been.

He was born on August 12, 1949, in Emporia, Kansas, the second of five children. His father, Mark Henry Essex, was a World War II veteran and foreman at the Fanestil Meat Packing Company, and his mother worked with disadvantaged preschool-aged children. The family was tight-knit and very Christian. Indeed, Essex had even considered becoming a man of the cloth at one point. Later in life, he would tell the minister who baptized him that "Christianity is a white man's religion."

"'and the white man's been running things too long,' Essex said.

"the upland prairie town took its name from ancient carthage. a young publisher named George Washington Brown encountered a reference to emporia, 'a flourishing market center on the african coast and founded by the greeks,' in a history book. it seems he thought it fit the optimistic outlook of the people who settled it in 1857.

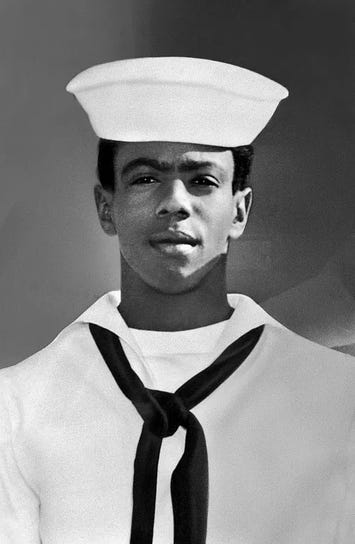

Essex enjoyed a childhood and adolescence devoid of racial acrimony. He was a Cub Scout with friends of all hues, stayed out of trouble and did alright in school. Classmates remembered him as a cheerful, smiling kid. He stood around 5'4," but he was fit. A friend who was also Essex's flag football coach described him as "a pretty good athlete, small and a little thin but he was very fast and had good moves," and "a happy-go-lucky kid."

After graduating from high school, he briefly attended college before giving all that up and doing a short stint at the same plant where his father worked. But the world called to him. Essex had dreams beyond the prairie. His father encouraged him to enlist in the military, which he did shortly after turning 19. That was his ticket out. The Navy sent him to San Diego, California, for training.

All things considered, he had it pretty good.

The day after Essex enlisted with the Navy, First Lieutenant John E. Warren Jr., a black U.S. Army officer, hurled himself on an enemy grenade in Vietnam's Tây Ninh Province. Warren saved three men with that act of valor and posthumously received the Medal of Honor. Essex, in contrast, would be spared the green inferno. Instead, he attended dental technician school before being assigned to the Imperial Beach Naval Air Station, near some nice beaches and the border with Tijuana, Mexico, whose bodegas he and his friends would occasionally hit up for drinks.

By all accounts, he excelled through basic and advanced training.

Essex formed a close bond with his white supervisor, Lieutenant Robert Hatcher, who was impressed with the young sailor's work ethic and dedication. "When Mark checked aboard, I signed him up for the flag football team I coached," Hatcher said.¹

He was a good team man, sort of an all-American boy. In those days he was just about the nicest person in the world. He was concerned about everybody around him, concerned about learning his job. I had one assistant who was better, but the kid had much more experience than Mark. He was the kind of person I liked to have around, a happy-go-lucky kid who was very hard to get rattled . . . Mark and I were about as close as an enlisted man and officer could be. Very frankly, we really threw a lot of b.s. out the window.

Other coworkers offered similar descriptions of Essex, "an easygoing guy" who would "sing to himself and be real friendly with everyone."

However, it was during Essex's time in the Navy that the seeds of hatred for whites were sown in his heart.

In letters home, he wrote about discrimination and bullying. Essex seemed unprepared for dealing with the world outside Emporia. His idyllic upbringing left him emotionally and psychologically ill-equipped for it. He developed a short fuse. On one occasion, he started a fistfight with another sailor over a slight provocation. The "riding" got to him. Extra bed checks. Extra guard duty. Soon, he started to take sedatives out of the medicine chest to deal with his nerves.

Hatcher acknowledged Essex's concerns and staunchly vouched for him in disputes. He said Essex underwent a "drastic shift" that was "very sudden," and suspected that the sailor fell under the influence of black militants:

The change was very sudden; it seemed to come in a matter of weeks . . . I remember joking with him about getting a ticket on the freeway, and he thought that the "white honky" was after him and we kind of joshed it off. But the problems seemed to start happening then. I have a feeling that he got in with a group of blacks who really felt they were being put down. And I don't think it was just based oriented.

Hatcher added that Essex talked about meeting in person with "guys who were putting out an underground newspaper." He advised his protégé to stay above it and focus on work opportunities. Essex listened for a time, and he quickly advanced in rank.

Then Essex abruptly took a defensive and belligerent turn, one that put him on a path that would end in blood and tears...

1 comment:

Pedro Gonzales wrote this...lol. The story is interesting,but what's Pedro's motivation in writing such a story? That might be even MORE interesting.

--GRA

Post a Comment