was it better to be in the eastern bloc?

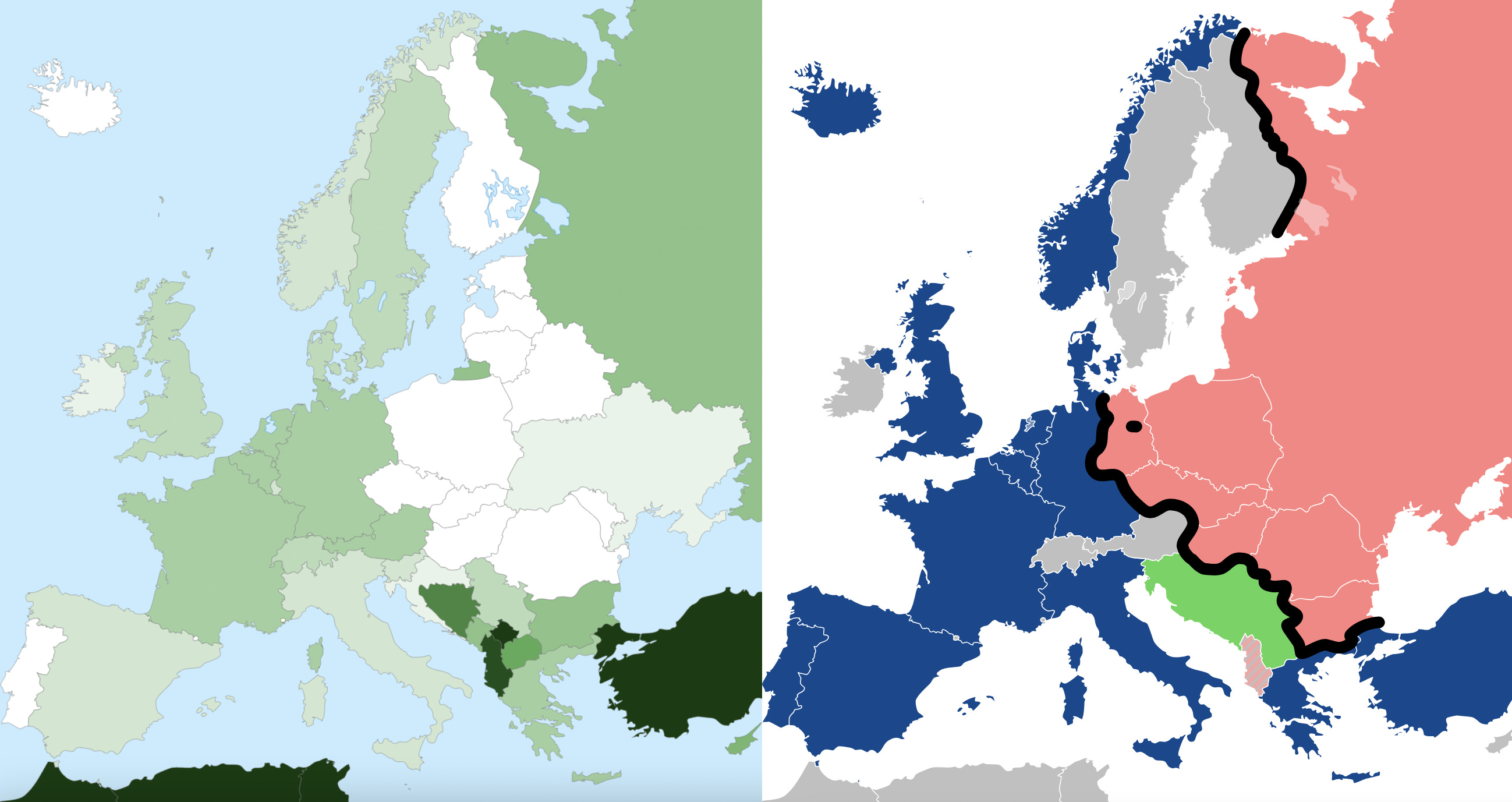

Life was worse under communism. But if we judge the two systems on a longer time scale, it's far from clear the Western one was more successful.Written by Noah Carl. Communism failed in Europe, just as it failed elsewhere. It was a grossly inefficient system that could only be maintained through massive coercion, repression and propaganda by the state. When the Berlin Wall came down, the countries of Eastern Europe were substantially poorer than their Western counterparts, and their populations had endured almost half a century without basic civil liberties.¹ I think we can say with some confidence that it was better to be in the Western Bloc. But what if we judge the two systems on a longer time scale? And what if we use an alternative, perhaps more fundamental metric of success: the extent to which they preserved the peoples and cultures that lived under them. Consider the two maps below. The one on the left shows Muslim population shares in different European countries. The one on the right shows the division between NATO and the Warsaw Pact (Yugoslavia, shown in green, was part of the Non-Aligned Movement). Ignore the Balkan countries (which have had sizeable Muslim populations for centuries, a legacy of the Ottoman Empire) and Russia (whose Muslim-majority regions are located outside of Europe). The correspondence between the two maps is remarkable. There's an almost perfect correlation between Muslim population shares and membership in the Western Bloc. Pew Research has made projections of the Muslim population in different European countries up to 2050. If they prove accurate, the correspondence between the two maps will become even closer. Under Pew's "medium migration scenario", the Muslim population will remain at or below 1.3% in every Eastern European country (aside from Bulgaria, formerly part of the Ottoman Empire). But it will reach 15% in Belgium, 17% in France and 20% in Sweden. Note that the left-hand map would look much the same or even starker if instead of Muslim population shares it showed the share of the population comprising all people of non-native origin (e.g., the total share of the French population comprising people of non-French origin). As far as I'm aware, no such map exists due to the lack of harmonised data. But we can be fairly sure it would resemble the left-hand one above. The correlation even holds within Germany – the one country that was split between the Eastern and Western blocs. This is shown in the maps below for Turks and Arabs, respectively. Note that these maps refer to foreign citizens, not naturalised Germans. But since immigrants tend to settle where there are already communities of their co-ethnics, the maps likely reflect the overall distribution of Turks and Arabs in Germany. What explains the correlation between demographic change and membership in the Western Bloc? The most obvious reason is that the Eastern Bloc countries maintained very restrictive migration policies throughout the Cold War. With the exception of a small number of communist dissidents from the West, such as the British-born Soviet spy Kim Philby, almost no one was allowed either in or out. Restrictions on emigration were designed to prevent all the productive people from leaving. But why did the Soviets restrict immigration? As this 2012 paper notes, they did so for three reasons: to exclude potentially disloyal citizens; to maintain ideological cohesion; and to control the information their citizens had about the outside world. Meanwhile, the countries of the Western Bloc opened their doors to large numbers of non-Western migrants – ostensibly to address labour shortages after the war. South Asians and Caribbeans went to Britain; Arabs and Africans went to France; Arabs and Turks went to Germany. Such migration flows then accelerated when the Cold War ended. In fact, in England's 1991 census, the two main Muslim groups (Pakistanis and Bangladeshis) comprised just 1.3% of the population. And the total Muslim population was probably no more than 1.5% (the 1991 census did not include a question on religion). Fast forward to the 2021 census, and England's Muslim population had risen to 6.5% – a fourfold increase in only 30 years. Returning to the Eastern Bloc countries, they maintained restrictive immigration policies even after the Cold War ended. Despite large refugee inflows from places like Iraq, Iran, Syria, Libya and Afghanistan – and considerable pressure from EU institutions – they've steadfastly refused to resettle Muslim migrants. The increasing demographic divergence since 1990 suggests that restrictive migration policies under communism can't be the only reason why demographic change correlates with membership in the Western Bloc. One possibility is as follows. The former Eastern Bloc countries would have embraced mass migration once they transitioned to capitalism, but having witnessed the effects of such migration in the Western Bloc countries (race riots, the Rushdie Affair) their citizens opted for demographic stability instead. So mass migration had a direct effect on the relative amount of demographic change in the two Blocs, as well as an indirect effect – by causing Eastern Bloc countries to change less than they otherwise would. But this prompts the question: why didn't citizens of the Western Bloc, having witnessed the effects of mass migration in their own countries, start opting for demographic stability too? One answer is that there's a certain amount of path dependency in demographic change because of chain migration. Once migrant communities become established, members of those communities bring their relatives in, and prospective immigrants find it more attractive to come. Or in other words: once migration starts, it's difficult to stop. Another possibility is that, having just regained their freedom after decades of communist rule, citizens of Eastern Bloc countries had little appetite for risk and therefore didn't feel like experimenting with mass immigration – regardless of what had happened in the Western Bloc. In this case, one would say that mass migration had a direct effect (but not an indirect effect) on the relative amount of demographic change, and that the legacy of communism also had an effect. Yet another possibility is that elites in the Eastern Bloc wanted to pursue mass immigration, but they simply couldn't convince voters who'd become deeply suspicious of utopian-sounding arguments after years of communist propaganda. The lies and false promises to which they'd been exposed inoculated ordinary citizens against high-minded appeals to the equality and mutual compatibility of all cultures. This would again represent an effect of communism's legacy on the relative amount of demographic change in the two blocs. One theory that's often brought up is that the relatively high proportion of Christians in countries like Poland and to a lesser extent Hungary has acted as a bulwark against Muslim and other forms of non-Western immigration. The problem with this theory is that it doesn't really work. Czechia and Estonia are among the least religious countries in Europe, yet they have among the lowest Muslim population shares, along with relatively anti-immigration attitudes as measured in surveys.² So far, I've been discussing explanations for the demographic divergence between East and West Europe that go back no further than the Cold War itself. But what if the divergence is rooted in much older differences? You may have heard of something called the Hajnal line, which runs from Trieste in Italy to St. Petersburg in Russia. It was drawn by the demographer John Hajnal in 1965 to demarcate areas where the "Western European marriage pattern" prevailed. Various individuals, such as the blogger HBD Chick, have argued that Europeans living in these areas evolved slightly different psychological traits than their counterparts living on the other side of the Hajnal line. Specifically, they evolved to be more individualistic, more trusting and more cooperative with people outside their immediate family. This hypothesis was formally tested by Jonathan Schulz and colleagues in a paper published in Science a few years ago. The authors found that people from countries and regions of Europe that spent more years under the influence of the Medieval Western Church prior are more individualistic, independent and prosocial today. As for proposed mechanisms, the Church implemented a series of policies (such as banning cousin marriages, arranged marriages and polygyny) which had the effect of breaking up the kin networks that had previously shaped people's psychological tendencies.³ In a letter responding to Schulz and colleagues' paper, anthropologist Peter Frost suggests that the Western European marriage pattern actually predates the policies of the Church, which was merely "assimilating the behavioral norms of its newly converted peoples". On the basis of such evidence, one could argue that Western Bloc countries would have had higher levels of non-Western immigration than Eastern Bloc countries even if the Iron Curtain had never come down, and that the post-1990 demographic divergence between the two blocs is attributable to pre-existing differences rather than anything that happened in the Cold War.⁴ There is surely something to this argument. But I don't think it can be the whole story: while pre-existing differences may have contributed to the demographic divergence between the two blocs, I suspect that what happened in the Cold War also played a role. To begin with, although Western Europeans probably are more "impersonally prosocial" than Eastern Europeans, they haven't always been more altruistic towards outsiders. Two of the most ethnocentric regimes in modern history –the Nazis and the Fascists – arose in Western European countries. In the case of the Nazis, they literally tried to exterminate whole ethnic groups they didn't like. Which is rather hard to reconcile with the claim that Germans have a predisposition to be altruistic towards outsiders. What's more, both Russia and Belarus have very low levels of kinship intensity according to Schulz and colleagues' data – lower than almost all the countries in Western Europe. Russians and Belarusians therefore ought to be among the most "impersonally prosocial" and altruistic towards outsiders. Yet they are not. As noted in the first part of this essay, the Soviet Union's immigration policy during the Cold War was extremely restrictive.⁵ What seems likely to me is that if the Iron Curtain had never come down, there would still have been some demographic divergence between the two blocs but not nearly as much as has actually taken place. Indeed, I suspect that the legacy of communism had a sizeable effect through one or more of the following channels: very restrictive immigration policy during the Cold War; risk aversion following the transition to capitalism; and resistance to utopian-sounding government propaganda. During the Cold War, life was clearly better in the Western Bloc than in the Eastern Bloc – which is why the GDR had to build a wall to keep their citizens in, rather than the other way around. But if demographics are destiny, the peoples and cultures of Eastern Europe may end up lasting longer than their Western counterparts. "We will bury you," Nikita Khrushchev told Western diplomats in 1956. The remark was widely misinterpreted as a military threat, and it's now generally accepted that he meant, "We will outlast you". Khrushchev was referring to the Eastern Bloc's communist system so in that sense he was clearly wrong. But re-interpreted in light of current demographic trends, the remark could prove very prescient. Noah Carl is an Editor at Aporia Magazine. Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription: 1 It should be noted that communist countries in Europe were far richer than communist countries in Asia. 2 Note that anti-immigration attitudes as measured in surveys do not always correspond to government policy or population demographics. For example, countries with high levels of immigration may have more anti-immigration attitudes than countries with low levels of immigration precisely because they have high levels of immigration. One shouldn't conclude that countries with less anti-immigration attitudes are therefore "more friendly" to immigration. In fact, the opposite may be true. 3 Unlike HBD Chick, Schulz and colleagues are "largely agnostic" regarding the role of genetic versus cultural evolution. 4 There were even important differences between East and West Germany before the Second World War. 5 In addition, several former Eastern Bloc countries like Czechia and Slovakia had very high exposure to the Western Church – higher even than the Nordics. |

Tuesday, April 02, 2024

Is the former eastern bloc NOW going to "bury" the west?

----- Forwarded Message -----

From: Aporia Magazine <aporiamagazine+isf-blog@substack.com>

To: "add1dda@aol.com" <add1dda@aol.com>

Sent: Tuesday, April 2, 2024 at 01:52:50 PM EDT

Subject: Was it better to be in the Eastern Bloc?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

When Whites countries are ruled by commies,they're worse off than they'd be under capitalism.But if the commies came over here now,they couldn't do a better job of destroying America than the Mex invaders,the blacks who expanded into our cities and the White liberals who pushed/allowed it all to happen.

--GRA

If you enjoy reading about the Cold War or fact based espionage thrillers, of which there are only a handful of decent ones, do try reading Bill Fairclough’s Beyond Enkription. It is an enthralling unadulterated fact based autobiographical spy thriller and a super read as long as you don’t expect John le Carré’s delicate diction, sophisticated syntax and placid plots.

What is interesting is that this book is so different to any other espionage thrillers fact or fiction that I have ever read. It is extraordinarily memorable and unsurprisingly apparently mandatory reading in some countries’ intelligence agencies’ induction programs. Why?

Maybe because the book has been heralded by those who should know as “being up there with My Silent War by Kim Philby and No Other Choice by George Blake”; maybe because Bill Fairclough (the author) deviously dissects unusual topics, for example, by using real situations relating to how much agents are kept in the dark by their spy-masters and (surprisingly) vice versa; and/or maybe because he has survived literally dozens of death defying experiences including 20 plus attempted murders.

The action in Beyond Enkription is set in 1974 about a real maverick British accountant who worked in Coopers & Lybrand (now PwC) in London, Nassau, Miami and Port au Prince. Initially in 1974 he unwittingly worked for MI5 and MI6 based in London infiltrating an organised crime gang. Later he worked knowingly for the CIA in the Americas. In subsequent books yet to be published (when employed by Citicorp, Barclays, Reuters and others) he continued to work for several intelligence agencies. Fairclough has been justifiably likened to a posh version of Harry Palmer aka Michael Caine in the films based on Len Deighton’s spy novels.

Beyond Enkription is a must read for espionage cognoscenti. Whatever you do, you must read some of the latest news articles (since August 2021) in TheBurlingtonFiles website before taking the plunge and getting stuck into Beyond Enkription. You’ll soon be immersed in a whole new world which you won’t want to exit. Intriguingly, the articles were released seven or more years after the book was published. TheBurlingtonFiles website itself is well worth a visit and don’t miss the articles about FaireSansDire. The website is a bit like a virtual espionage museum and refreshingly advert free.

Returning to the intense and electrifying thriller Beyond Enkription, it has had mainly five star reviews so don’t be put off by Chapter 1 if you are squeamish. You can always skip through the squeamish bits and just get the gist of what is going on in the first chapter. Mind you, infiltrating international state sponsored people and body part smuggling mobs isn’t a job for the squeamish! Thereafter don’t skip any of the text or you’ll lose the plots. The book is ever increasingly cerebral albeit pacy and action packed. Indeed, the twists and turns in the interwoven plots kept me guessing beyond the epilogue even on my second reading.

The characters were wholesome, well-developed and beguiling to the extent that you’ll probably end up loving those you hated ab initio, particularly Sara Burlington. The attention to detail added extra layers of authenticity to the narrative and above all else you can’t escape the realism. Unlike reading most spy thrillers, you will soon realise it actually happened but don’t trust a soul.

Post a Comment