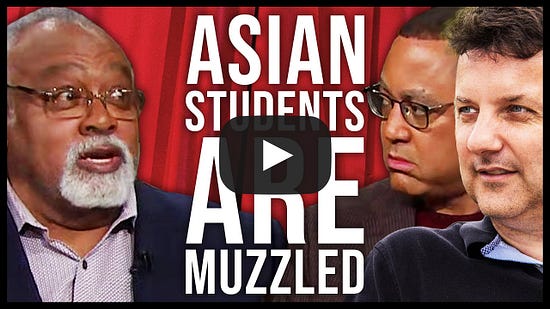

One of the more interesting footnotes to the Students for Fair Admissions case doesn't involve what happened. It involves what didn't happen. After the decision came down, liberals and the left voiced their dismay at the result. There was a little organized protesting, but it was nothing compared to the massive waves of mobilization that attended the Dobbs decision on abortion, despite the fact that the result was predictable in both cases. Perhaps that's to be expected. Dobbs is, in my view, the more consequential decision. It has the potential to directly affect far more people than Students for Fair Admissions. But I think there is another factor at play. Most people already suspected what the latter case demonstrated—that race-based affirmative action is a discriminatory practice. It was both unjust and unpopular, and now it's been declared unconstitutional. The relatively muted response from some of the left could signal a tacit decision to relinquish the legerdemain and enforced silence and bad faith necessary to keep the policy going. I can't help but think that, whatever attitude they present to the public, some affirmative action defenders are secretly relieved that they can now turn their attention elsewhere. Of course, I'm only speculating. And the fight over racial preferences in college admissions is not nearly over. It's too big a business to simply vanish; elite institutions have invested too much in it to just give it up. This week's episode features Duke economist Peter Arcidiacono, the man who led the herculean effort to analyze the data that made Students for Fair Admissions' case. As Peter says, that data is clear. Now that it's out in the open, any of the "good liberals" who defended affirmative action as a matter of principle while privately harboring doubts as to its logical and moral coherence have an offramp. They can let it go. The questions is, will they? This is a clip from the episode that went out to paying subscribers on Monday. To get access to the full episode, as well as an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below. GLENN LOURY: Peter was the main guy—correct me if I get anything wrong, Peter—in the data analysis marathon that had to be undertaken in order to parse through the information made available by Harvard University, quantitative information on its admissions policies, what exactly was going on. And he faced off against the estimable David Card—Nobel fame, UC-Berkeley—who was the lead witness for the defendant, Harvard University, in the litigation. And he prevailed. PETER ARCIDIACONO: Not at first, but in the end, yes. So what were the scientific questions, the academic questions, which you've been engaged with that were relevant to the litigation. PETER ARCIDIACONO: Well, what was relevant to litigation was, was there a penalty against Asian Americans? And also how big the preferences were at these different schools. JOHN MCWHORTER: There's nothing sadder than the position of an individual Asian student today at these universities. They are so muzzled. You can often tell what they do think about all of this, but you can't say that in their social circles. And so they don't. I've seen a couple of them actually change color as they talk about it. It's weird. I told one of them, I'm sorry that you are in selective university at this time, because this must be a really tough thing to have any kind of constructive conversation about. Except, I imagine, among yourselves. And one of them kind of smiled. I mean, you can tell what's going on. It's hard, but this had to happen. It was time. Peter, I'm glad that you did this. What in your gut got you onto this? Because, of course, some people are going to say, "Peter, it's just racism," and there's a certain kind of crowd who will applaud. I know it's not that, but what interested you about this? PETER ARCIDIACONO: Well, I think that came about through my own experience as an undergraduate and seeing how much easier the economics classes were than the chemistry classes, so then studying higher education. And then back in 2011 when there was a protest over one of my papers on this, seeing universities not really willing to engage in dialogue about how best to improve the experiences here. That probably set me on this path. What that paper showed was, it was really about a data fact. You look at white males, they come in, those who want to do STEM and economics, they switch out at a rate of eight percent. This is at Duke. Black males interested in STEM and economics switch out at a rate of over fifty percent. And nothing happened after that. You know, we just sort of let the protests happen, everything sort of died away, nothing changes. And I think it relates, actually—I know you wrote about this—the Georgetown Law professor who got caught on video lamenting the poor performance of her black students. Sandra Sellers.

PETER ARCIDIACONO: And she got torn to pieces. And to me, that's a feature not a bug for affirmative action. When you come in, you're going to be behind your peers. That's by definition, unless we're screening on things that we shouldn't be screening. So that idea, you're going to come in behind, the performance relative to your peers is going to be worse. It could still be a good thing that you're going to the better school and have a better outcome. But it's a definite feature of the system that you will be further down on the last rank. So now you have a system where actually they come in with the university saying, "We want you so much. We're willing to give you big preferences." And they come out thinking the place is racist. That doesn't seem so good. JOHN MCWHORTER: It's not so good. It makes no sense whatsoever. It's one of the aspects of all of this that really is as peculiar as discussions medieval Europeans had about matters of religion and philosophy, where again, you have to be very careful to understand what the terminology is, what things you're not supposed to look at and why. Truly peculiar that you have that kind of preference, and yet the stylish attitude by the time you're finished is that you've just gone through some sort of racist hazing. And it really will perplex people in say a hundred years, maybe even in fifty, to look back on the state of our discussion with this and to see something like what Sandra Sellers was lamenting. And for the good thinking idea to have been that there's nothing wrong with that, that that's not something that we need to try to fix, and it doesn't matter. Yes it does. And I think that everybody will understand why a few of us weird renegades back in the early twenty-first century thought it did. It does. I think it's going to happen a lot quicker than fifty years. I think it's happening before our very eyes. I mean, Peter pointed out that this decision, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and the University of North Carolina, did not engender the same kind of backlash from the left of revulsion and political determination to do something about it that the Dobbs decision on the abortion question did, even though it is resolving in a "conservative" direction of one of the big questions of constitutional law of the last half-century. It is historic in representing a kind of transformation of the law in its way, as was the Dobbs decision. It didn't engender the same kind of backlash. And I think this house of cards which Peter described—I mean, the Sandra Sellers thing is a predictable consequence. As he says, it's a feature, not a bug. It's a predictable consequence. And then you're going to have a witch hunt and you're going to go around and cut people's heads off if they observe that it's true. And then everybody can see it. It's not like it's not common knowledge that there are these implications of preferences. It's corrupt. I think Justice Clarence Thomas deserves to be recognized here as, for decades, having made this argument about the affront to the dignity of the beneficiaries of preference, the fact that they're not being taken seriously as persons of whom it is reasonable to expect performance like anybody else. You're patting the beneficiaries on the head. You're turning them into baubles to wear on a charm bracelet around your wrist, representing the various colors of the demographic universe. You're not taking them seriously. That's what I would say. |

Tuesday, July 25, 2023

Giving up the bad faith of affirmative action

----- Forwarded Message -----

From: Glenn Loury <glennloury+the-glenn-show@substack.com>

To: "add1dda@aol.com" <add1dda@aol.com>

Sent: Tuesday, July 25, 2023 at 02:46:00 PM EDT

Subject: Giving Up the Bad Faith of Affirmative Action

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

" It was both unjust and unpopular, and now it's been declared unconstitutional. "

At yet somehow, someway, the left and the liberal will find a way around Dobbs.

Post a Comment