Re-posted by Nicholas Stix

The mystery of Joachim/Jochen Peiper isn’t his death (as opposed to his killers’ identities), but why did U.S. Gen. H.I. Hodes parole Peiper away from his date with the executioner?

Years after the Battle of the Bulge and the infamous Malmedy Massacre, Joachim Peiper died under mysterious circumstances in Traves, France

By Michael ReynoldsWarfare History Network

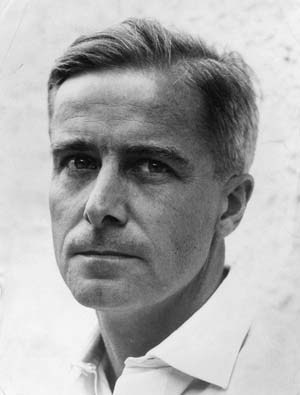

One of the foremost German characters in the Battle of the Bulge was Obersturmbannführer (Lieutenant Colonel) Joachim Peiper, the notorious Waffen-SS commander of the strongest armored Kampfgruppe (KG) of the 1st SS Panzer Division, Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler (LAH). It was his KG of 117 tanks, some 700 other vehicles, and nearly 5,000 men that Hitler had intended should reach the Meuse River first, but he failed and, after 10 days of intense fighting, was forced to escape through American lines with no heavy equipment and only 800 men left.

Even so, Peiper received swords to his Knight’s Cross for his part in his beloved Führer’s last great offensive in the west. After the war he was labeled “GI Enemy Number One” for his alleged part in the Malmedy Massacre of American prisoners, and to this day he is remembered by most Americans, and certainly by all Bulge veterans, as a condemned war criminal whose murder in France in 1976 is seen as poetic justice for the man they believe cheated the hangman’s noose in 1946. To his German comrades, however, his murder made him the last of the fallen—the last casualty of the famous unit in which he had served for nearly 11 years; and to neo-Nazis and to those with Fascist and far right tendencies he has become a hero whose memory is revered.

Sentenced to Death

On July 16, 1946, at the former concentration camp at Dachau in Bavaria, Joachim Peiper was sentenced to death by hanging for his part in the deaths of 71 surrendered American soldiers at a crossroads near Malmedy, Belgium, on December 17, 1944. The following day he was moved to the fortress at Landsberg—the same prison where Adolf Hitler had been imprisoned in 1925 and had written Mein Kampf.

What happened to this charismatic, if blemished, soldier after his release? Peiper’s parole, ordered by the U.S. commander in chief in West Germany, General H.I. Hodes, was to last until May 21, 1980, and he was to be restricted to the Stuttgart area. He was required to report to his American parole officer, Paul J. Gernert, on the 1st and 15th of each month. His wife, Sigurd, and his three children had remained in their house in Rottach am Tegernsee for the first part of Peiper’s imprisonment in Landsberg, but in November 1955 she moved to Sinsheim in Baden-Württemberg to be closer to him. Until she could move again to the Stuttgart area, Peiper was allowed to visit his family only on weekends and holidays and by the most direct route.

While in Landsberg, Joachim Peiper had earned an interpreter’s diploma in English and had worked in the prison garden and the motor pool and had done some book binding; but in real terms, apart from his knowledge of English, he had no qualifications for civilian employment. His German parole supervisor was a Dr. Theodor Knapp, and his sponsor was Alfred de Maight, the personnel chief of the Porsche Motor Company—at least he had one useful contact and, not surprisingly, he was soon given a job as a clerk in the vehicle assembly and construction office of the company in Zuffenhausen. His first postwar home was as a tenant of a Dr. Hartmann in Klagenfurtstrasse 4, Stuttgart.

A Bitter, Disillusioned Old Man

By 1956 Peiper was a bitter and disillusioned man. He had witnessed the collapse of his whole world, the Third Reich, and in particular the “family” to which he had given his adult life: the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler. The motto of the Leibstandarte had been “My honor is my loyalty,” and yet this loyalty, which had sustained him and his comrades through nearly six years of fighting, had finally collapsed at the U.S. Interrogation Center at Schwabisch Hall —even his former adjutant had testified against him.

In 1948 Peiper said, “From this moment on everything was a matter of indifference to me. My confidence in our comradeship was broken and I felt only physical disgust against my Adjutant.”

Working for Porche [sic] & Volkswagen

Peiper was released from parole on June 21, 1958, and three years later his obvious talents were recognized when Ferry Porsche, the head of the company, appointed him company secretary. He was the first nonfamily member to get the job, but this promotion brought Peiper to the attention of the powerful union, IG Metall. Ferry Porsche was told that while the union could tolerate a former condemned war criminal as a clerk, it would not accept Peiper as part of the management and would start an adverse publicity campaign if he was confirmed in the position. Porsche had little option other than to cancel the appointment. Peiper threatened to sue the company but eventually settled for six months’ salary as compensation. But worse news was to come. The union made it clear that he would be similarly hounded out of all other companies in which they had workers.

Peiper then became an independent sales promoter, first for a Volkswagen dealer in Reutlingen and later in the same capacity in Offenburg and Freiburg. He also did some sales promotion work for a carpentry firm in Offenburg. By April 1967, he was back in Stuttgart, living at Schnellbachstrasse 32, but doing the same work. In a prophetic interview with a French writer in the same year he made his feelings clear:

“I was a Nazi and I remain one…. The Germany of today is no longer a great nation, it has become a province of Europe. That is why, at the first opportunity, I shall settle elsewhere, in France no doubt. I don’t particularly care for Frenchmen, but I love France. Of all things, the materialism of my compatriots causes me pain.”

New Court Hearings in 1968

On December 11, 1968, Peiper and two of his former officers were accused in a German court of killing Italian civilians in 1943. The Italian authorities and nine plaintiffs brought the case from a small town in northern Italy called Boves. Peiper’s unit had been stationed in the area after taking part in the disarming of the Italian Army in August 1943, and the accusations stemmed from an incident the following November when two of his NCOs had been kidnapped in the town, allegedly by Italian soldiers.

When their company commander radioed that he had been attacked by superior forces, Peiper reacted characteristically by leading the rest of his battalion to the rescue. On arrival he shelled the town with 150mm guns, and this had the required effect. Peiper got his men back, but 34 Italians died in the process. The court received depositions from 17 Italians and 126 former members of his battalion and ruled in February 1969 that there was insufficient evidence for formal charges to be laid.

Moving to Traves

During the winter of 1970-1971, Peiper moved to a small house he and his wife had had built on their land by the Saône River in Traves. The French authorities, who had full knowledge of his identity and background, granted him a residence permit on April 27, 1972, which was initially valid until February 27, 1977.

The Peipers were not well off, but their children were grown up and had left home and they could live quite well, if quietly, at Le Renfort (The Reinforcement) alongside the other 280 inhabitants of Traves. The house was roughly 400 meters from the edge of the village, and their nearest neighbor was about 250 meters farther west. The owner was a former Leibstandarte artillery captain named Erwin Ketelhut.

Le Renfort was built on a high bank above the river and lay well back from the country road leading into the village. It was a modest three-bedroom house with vestibule, cloakroom, kitchen, living room, and study on the main floor and a utility room and bathroom on the lower ground floor. There was a terrace along the side of the house and a veranda at one end, next to the study. High trees gave it seclusion, and a barbed wire fence separated Peiper’s land from a meadow that lay between it and the village road. At this time his son, Heinrich, was a solicitor in Frankfurt, daughter Elke, a professor in Munich, while his youngest daughter, Silke, was resident in Hamburg.

Discovered by the Locals

Although the Peipers kept to themselves, the few contacts they did have in the village are said to have been friendly—at least until the “hate campaign” started in June 1976.

On June 21, leaflets were distributed throughout Traves: “People of Traves, a war criminal, SS Peiper is amongst us!” The text went on to call for his expulsion from France, and the following day the national newspaper l’Humanité printed an article on the same lines. Within a few days most of the French and even some international newspapers joined in, and walls and road surfaces in the area were daubed with swastikas, SS runes, and Peiper’s name. In a carefully orchestrated campaign the Communists claimed that in exposing Peiper’s background to the public they were merely expressing the indignation of the population.

Peiper complained to the French police in Vesoul, and they agreed to provide a guard—but in the daytime only. The West German embassy in Paris had nothing to offer but sympathy and advised him to leave the area, at least temporarily.

On June 23, Peiper was interviewed by a French newspaper reporter. When asked about his Nazi past he replied, “That is a ridiculous question…. I was young and idealistic against Bolshevism. I do not understand why people keep dragging up history. As the Italians say, ‘The coffee is cold.’ Today, it is time for reconciliation in Europe.”

And when asked about his association with the SS, he said, “I was not political. I was never a member of the Nazi party. I was a soldier.”

Threats of Arson Before the Fire

On July 13, Peiper received letters and telephone calls telling him his house and dogs would be burned. There was no direct threat to kill him. Sigurd left the same day in the BMW. It is not clear exactly where she went. Arndt Fischer told the author in 1991 that she had a long-standing arrangement to visit an old friend in Strasbourg and that Peiper had encouraged her to keep the appointment. This may well be true, or she may possibly have gone to her son in Frankfurt. She and Heinrich appeared together in Vesoul on July 15, 1976—the day after Peiper’s death.

After his wife left, Peiper wrote two letters. In the first, to Rudolf Lehmann, the former chief of staff of the 1st SS Panzer Division and a personal friend, he said that his “quiet haven” had become “an entrenched camp” and that he would “move in the autumn if the Communists allow me to wait until then.” The second was to another old friend, Dr. Ernst Klink, of Waldkirch near Freiburg. Klink was another former Waffen-SS officer who, after the war, had worked in the federal military archives in Freiburg.

Peiper wrote that, owing to “uncertainties in Franco-German relations,” he had stopped writing his book and was therefore sending him the existing material. He went on to say that if Bettina Wieselmann came to see him, he should give her every assistance.

Later the same day, Peiper and Ketelhut discussed the overall situation. Peiper said he was not particularly worried because he did not believe the people making the threats were particularly courageous; and anyway he had a Colt .38 revolver and a .22 rifle with which to defend himself. Ketelhut offered to lend him a Remington 12-bore shotgun, which he accepted, and to keep an eye on the area that evening from his balcony at the mill. He took the precaution of equipping himself with two loaded rifles.

Sirens on Bastille Day

At about 11:30 pm, Ketelhut, having heard and seen nothing suspicious, took a weak sleeping pill and went to bed. One and a half hours later, on Bastille Day 1976, he was awakened by the sound of the village siren and from his balcony he saw flames leaping from Peiper’s house.

When the local fire brigade was called out in the early hours of July 14, their pump was found to be unserviceable; the 11 firemen were questioned by the police but the pump was found to be genuinely defective and there were no traces of sabotage.

After the fire was eventually extinguished, the police discovered a badly burned body in the remains of the study. Due to the intense heat generated by the fire, it had shrunk to a length of about 60 cm and was barely recognizable as that of a human being. When Ketelhut was shown the body at 5 am the following day, he said: “It is him but he is miniaturized.”

Under the body the police found a fire-damaged .22 rifle with an expended case in the chamber and nearby a Colt .38 revolver with five expended rounds in the cylinder. A further 13 unexpended .38-caliber rounds were found in the same room. Out on the terrace they discovered three expended shotgun cartridges, a Remington 12-bore shotgun with an open, empty breech, and a strong smell of powder.

An examination of the garden revealed traces of shot near an oak tree about 10 meters from the house and a .38-caliber bullet at about the same distance from the veranda, between a pine tree and the kennel.

Both Peiper’s dogs had been wounded, and there were four 6.35mm bullets in the bloodstained kennel. A 6.35mm pistol is a very small weapon indeed, usually carried by ladies for self-protection.

Forensics Inconclusive

It appeared that the victim had tried to save some clothes belonging to Frau Peiper by throwing them out of the house, and in front of the veranda the police discovered a pair of binoculars and some personal papers, including Peiper’s last letter to his wife. Peiper’s watch, which was found on the body, had stopped at 1 am and a clock in the house at 1:07.

Two experts in arson, one from Lyon and the other from Marseilles, investigated the fire the day after the attack. They judged that it had started at the back of the house, the side nearest the road, and taken hold very quickly due to the wooden floors and ceilings. Three different sources of the fire were discovered, and one poorly made Molotov cocktail was found outside the house and the remains of three more in the study.

The subsequent criminal investigation was carried out by the Police Judiciaire of Dijon. The principal police commissioner was Monsieur Guichaux, and the chief inspector was named Casseboix. It was found that the wire fence between the garden and the meadow had been cut with wirecutters, and from the projected trajectories of the various weapons fired by the victim the police concluded that he had attempted to dissuade his attackers from firebombing his house by firing all three weapons at them. There was no evidence of any weapons being fired toward the house, and therefore no evidence of any direct attempt to kill the victim. There had been no attempt to cut the telephone line to the house.

In summary, it would seem that after firing the shotgun from the terrace to dissuade his attackers, Peiper reentered the house in order to save important personal papers and some of Sigurd’s clothes. Having thrown these out of a bedroom window and the study door, he then continued to defend himself and his property by firing his other weapons but was overcome by smoke and died in the fire.

The Body Destroyed

Not surprisingly, Sigurd Peiper wanted her husband buried in Germany, but before a German burial certificate could be issued a German autopsy had to be carried out. However, Arndt Fischer told the author in June 1991 that when the body arrived from France the head was missing. It appeared later but had been sliced up and the only tooth still present was split. The German autopsy was performed by Professor Spann of the Institute for Rechtsmedizin of the University of Munich, and Peiper’s body was finally laid to rest in the cemetery of St. Anna’s church at Schondorf am Ammersee in Bavaria, along with those of his father, mother, and two brothers.

Extraordinary scenes followed the events of July 14, 1976. After a claim the following day by an unknown group calling itself The Avengers, the London Times thundered: “Avengers kill SS colonel in France,” and three days later another prominent British newspaper reported: “Cars full of sightseers converged this weekend on the small village of Traves … to get a glimpse of the burnt out house of Joachim Peiper, the former SS colonel who perhaps is not dead.”

« Previous: “Pact of the Devils: The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.”

1 comment:

I have often thought it strange that such an infamous person as Peiper would move to France. Traves it appears was in the opinion of the Waffen SS high command to be the most ideal spot on the planet to retire to. This is why Peiper moved there? He must have known [?] he would be unmasked and threatened. And he was. It is all cold coffee now, isn't it.

Post a Comment